How the CIA Secretly Used Jackson Pollock to Fight the Cold War

This is the story of how Jackson Pollock became tangled up in America’s propaganda war with the Soviet Union. But it’s also a story about how a radical New York City art movement aligned with America’s economic and cultural dominance after World War II.

In the late 1940’s, a left-wing, avant-garde painter like Jackson Pollock would have seemed like a very unlikely candidate to receive support from the CIA. This was a time when many Americans, including President Harry Truman, loathed abstract, modern art. Americans, by and large, appreciated more traditional, realistic approaches to painting and were often mystified by the art of European painters like Pable Picasso. Add to this the fact that Jackson Pollock was suspected of communist ties, and the CIA’s backing of Pollock seems all the more improbable during the height of the McCarthy era.

Up until World War II, America had never produced large, influential art movements like in Europe. Most American artists during the 1920s and 1930s had conventional approaches to painting or if they did paint abstractly, they took their cues from Europe. But after World War II, something unexpected happened. A brood of radical, American painters, helped make New York City the new center of the art world. Artists like Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock captured the world’s attention with large-scale works of pure color and form. This style of painting was radical and new, and most importantly, it was a wholly American art movement. It was called abstract expressionism. And by the 1950s, this new American painting was the most exciting thing happening in the art world. But to the CIA, this American art movement represented a potential weapon in the fight against communism.

The wreckage of World War II left the United States and the Soviet Union as the world's two remaining superpowers; and the tensions that would eventually lead to the Cold War began immediately. The US found itself up against a massive Soviet propaganda machine. This was a war for hearts and minds; and by the late 1940s, a war that the CIA felt they were losing. The Soviets were spending $250 million a year on communist propaganda. And to make it worse, the CIA felt the Soviets had stolen all the best words like freedom, justice and peace. The CIA decided to make a massive push to promote American arts and culture –and Jackson Pollock and the abstract expressionists would find a special place in the CIA’s portfolio. The CIA realized they could use abstract expressionism to highlight the differences between American and Soviet politics. More specifically, they could highlight the appeal of American culture over Soviet culture. Because in this new war of ideas, the abstract expressionists evoked the most sacred American values, freedom and individualism.

The CIA’s plan makes perfect sense when one considers the state of Soviet art of the time. Beginning in the 1930s under Joseph Stalin, the USSR restricted Soviet artists to a single genre, socialist realism. This was an “official” style of art that idealized communist values and glorified the Soviet working class. The goal of the art was to promote solidarity and party loyalty. All Soviet art had to be realistic and could only portray Soviet life in a favorable light.

This clearly would not fly in America. No one was going to tell Jackson Pollock how or what to paint. He may have been sympathetic to communism, but Pollock’s art could not have been more antithetical to socialist realism. The very concept of abstract expressionism is all about the subconscious creation of the individual artist. Like the surrealists who came before them, abstract expressionists were interested in unlocking the deep mysteries of the mind. But unlike the surrealists, the abstract expressionists left any vestige of the representation behind. These paintings look like little that came before them. Pure abstraction. Nothing from the real world, only the inner world, manifested in color, shape and texture. And the paintings didn’t really look like each other either. The abstract expressionists seemed to be expressing themselves in unique, individualistic ways. Art was no longer about capturing an experience, it was, in the words of Mark Rothko, “the experience itself.”

Pollock’s paintings were particularly radical. His free flowing technique ignored the bounds of the canvas itself. Pollock chose to paint on the ground, without stretcher bars, flinging cheap house paint straight off the edges. This technique earned him the derisive nickname, Jack-the-Dripper. It was, in a way, the perfect vector for the CIA’s message of American freedom of choice over Soviet state restrictions. A former CIA agent named Donald Jameson said:

“It was recognised that abstract expressionism was the kind of art that made [the Soviet sanctioned] socialist realism look even more stylised and more rigid and confined than it really was. And that relationship was exploited in some of the exhibitions. Moscow in those days was very vicious in its denunciation of any kind of non-conformity to its own very rigid patterns. And so one could quite adequately and accurately reason that anything they criticized that much and that heavy- handedly was worth support one way or another."

The subjective, non representational nature of abstract expressionism made it very amenable to interpretation. So if the CIA, or influential art critics like Clement Greenberg wanted to attach anti-comminist, western values to abstract expressionism, well then the art allowed for it. And so Pollock really became the ultimate avatar for this new american art movement. A cowboy painter with an unchained id who seemed to exude American spirit. Pollock argued that “Painting is a state of being . . . painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.” Statements like this really show how divorced abstract expressionism was from any kind of politics or ideology.

So beginning in 1950, the CIA began actively promoting abstract expressionism. But this wasn’t something that could be done openly. Supporting artists with communist ties was just not tenable for the U.S. government. In 1946, the U.S. State Department had created a political firestorm by trying to directly sponsor modern, American artists, some of whom turned out to be members of the communist party. They then vowed to never again spend taxpayer money on abstract modern art.

The CIA instead opted for methods some might have considered morally questionable. Instead of sponsoring American artists directly as the State Dept had done, they secretly helped found an anti-communist advocacy group called the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Through this group, the CIA covertly funneled money to MOMA’s ( Museum of Modern Art) international art shows, funded a literary magazine in the UK called “Encounter,” and operated offices in thirty-five countries. This entire operation was dubbed “Long Leash” and its efforts were designed to target disaffected Soviets, intellectuals, artists, and anyone with communist sympathies. This operation also allowed the CIA to organize and promote art on America’s home front.

Thomas Braden, MOMA's executive secretary in the late 1940s was hired by the CIA to direct these cultural activities. He created a nexus between the U.S. propaganda machine and the elite New York art world. Braden, years later, described one of the ways in which money was channeled to the arts:

“We would go to somebody in New York who was a well-known rich person and we would say, ‘We want to set up a foundation.’ We would tell him what we were actually trying to do and pledge him to secrecy, and he would say, ‘Of course I’ll do it,’ and then you would publish a letterhead and his name would be on it and there would be a foundation. It was really a pretty simple device.”

Writer and cultural observer Louis Menand argued in his 2005 article for The New Yorker (“Unpopular Front”) that there was a more specific message that was meant for Soviets sympathetic to the west: You can be a left-wing artist or intellectual, openly criticize your own government, and still flourish in America’s free market and open society.

Ironically, In the 1950’s, the CIA was mostly made up of ivy league graduates who were far more liberal than other government agencies like the FBI. Many of them actually collected art, were versed in contemporary art of the day, and had associations with the Museum of Modern Art, the preeminent modern art museum in the United States. So whereas FBI director J. Edgar Hoover sought to persecute left-wing artists and intellectuals, the CIA chose to elevate them. The CIA reasoned that coercion would never win hearts and minds. The CIA ended up being quite successful anonymous patrons of leftist American artists, throwing several art shows of abstract expressionism in the 1950s through the Congress for Cultural Freedom. But the degree to which the CIA was successful is more difficult to ascertain.

By the 1950s Jackson Pollock had become the most famous living American artist and a symbol of America’s cultural dominance. And even though he divided critics and the public, it was pretty easy to associate Pollock’s unbound approach with American freedoms. In a way, the CIA simply amplified a message that had already been developed by prominent American art critics, that American painters were free to invent and offend and that their success was the result of a superior political and economic system built on freedom and individualism. Unlike Soviet artists, American artists were not simply propaganda tools parroting party values.

But there are a number of reasons for the success of abstract expressionism, and American art at large, beyond patronage from the CIA. America emerged from World War II as a superpower, while Europe was left in ruins. Money was pouring into the arts even without the help of the CIA. Leftist intellectuals such as art critics Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg saw communism as a threat to the independence of the artist. Greenberg saw America as a bastion of artistic freedom, and called Jackson Pollock the greatest painter of his generation. Nelson Rockefeller, a staunch anti-communist, donated huge sums to MOMA. He was happy to throw his weight behind original American art. For Rockefeller, this was a patriotic act.

And so, even though the general climate in 1950s America was very anti-commnunist, the climate for avant-garde American painters was becoming much more favorable, despite whatever political affiliations they had. Joseph McCarthy was censured by the U.S. senate in 1954 bringing an end to the McCarthy era. President Harry Truman was replaced by Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican no less, who appeared to be much more amenable to modern art. Eisenhower said:

“As long as our artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction, there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. How different it is in tyranny. When artists are made the slaves and tools of the state; when artists become the chief propagandists of a cause, progress is arrested and creation and genius are destroyed.”

Eisenhower was of course interested in winning the Cold War, not in protecting the creative process. His acknowledgment of modernism was part of a strategy to showcase America’s cultural vitality. Again, appealing to disaffected Soviets and left-wing Europeans who may not have viewed America as having “real culture.” Of course by the 1960's, Eisenhower would blame America’s moral decline on modern art and the dance craze “the twist,” while lamenting Michelangelo and Leonaro da Vinci’s fall from grace. But despite Eisenhower’s later pessimism, this whole enterprise feels like a win for the U.S. Post-war American arts flourished and U.S. culture took center stage. Abstract expressionism endures to this day as a major art movement.

But there are obviously major contradictions with the CIA promoting western values through secrecy and subterfuge. For the CIA to use the idea of American freedom simply as a tool to achieve a political end undermines the principles America was supposedly founded on, and was fighting for during the Cold War. But on the other hand, when the U.S. government tried to promote modern art openly, it was met by the wrath of McCarthyism. Thomas Braden mused that “back in the early 1950's, when the Cold War was really hot, the idea that Congress would have approved many of our projects was about as likely as the John Birch Society's approving Medicare.” And so the CIA found itself fighting the Soviet Union by subverting a large swath of the American political class, as well the American artists whose careers they were advancing.

Thomas Braden was anything but apologetic about his role in Cold War propaganda. He wrote an article titled “I’m glad the CIA is ‘immoral’ arguing that the secret promotion of American art and culture in Europe won more acclaim for the U.S, than Dwight D. Eisenhower could have bought with a hundred speeches. Braden would later star as the liberal voice on CNN’s Crossfire.

But let’s not forget, abstract expressionism truly was innovative in its own right. It was clearly a win for artists and intellectual freedom. Post-war American art in general was incredibly diverse. Many European avant-garde artists and intellectuals had left Europe for America. Artists like Hans Hoffman and Marcel Duchamp settled in New York City and helped establish the city as the new center of the art world where successive generations and movements would thrive, including conceptual art, pop art, and minimalism.

Even within movements like abstract expressionism, the work of different artists looked nothing alike. It was a deft stroke of ingenuity by the CIA to characterize this diversity as the product of freedom. But this should not diminish the real innovations of these American painters that include: Hans Hoffman, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Lee Krasner, Barnet Newman, Clyfford Still, Helen Frankenthaler, Willem de Kooning to name just a few. This was an exceptionally inventive time in art history. A period of so-called “pure painting” and “pure expression,” in which there was true belief in the power of painting to provide a metaphysical experience. Critics like Harold Rosenberg helped raise this approach to painting into heroic, mythological realms. Rosenberg described the abstract expressionist as an “heir of the pioneer and the immigrant,” a “vanguard painter [who] took to the white expanse of the canvas as Melville’s Ishmael took to the sea.” Painters like Pollock were lionized and romanticized and were immensely influential on later generations of art.

What does all this mean? Well it means the CIA’s role in the success of American modern art is difficult to quantify. Yes, the CIA integrated itself into the fabric of the post-war American art scene and were pulling strings, but they had a lot of willing partners. America’s cultural institutions were largely run by anti-communists and wanted to support American artists. But more importantly, the U.S. government was actually very open about its support of American culture. It was just the pesky modern artists with their radical aesthetics and communists ties that required a sneaky, less public strategy.

The history of art has long seen the entanglement of money, politics and power, and featured many strange bedfellows. From the Vatican hiring Caravaggio, a brawling, murdering tyrant, to help fill church pews during the counter reformation, to Jacques-Louis David’s revolutionary propaganda, commissioned by the soon to be beheaded Louis XVI. But the CIA's great invention was to allow the public to believe abstract expressionism was a completely independent, organic phenomenon, when it really wasn’t. Did the Abstract Expressionists have creative freedom? Yes. Was their art propaganda? Yes, from a certain point of view. But either way you look at it, the CIA surely had a hand in nudging the trajectory of western art in America’s favor, and the abstract expressionists burned hotter with help of American spycraft.

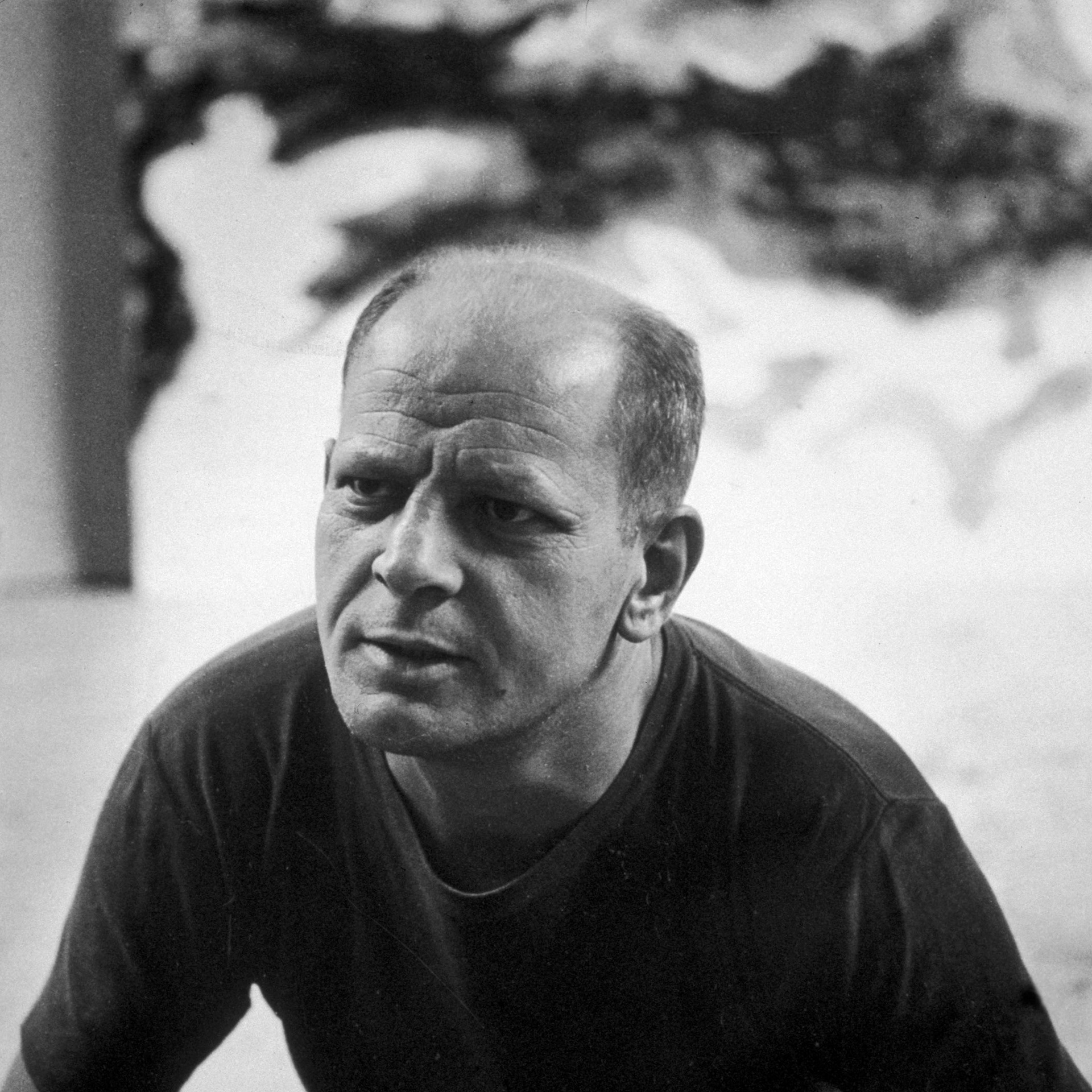

Jackson Pollock

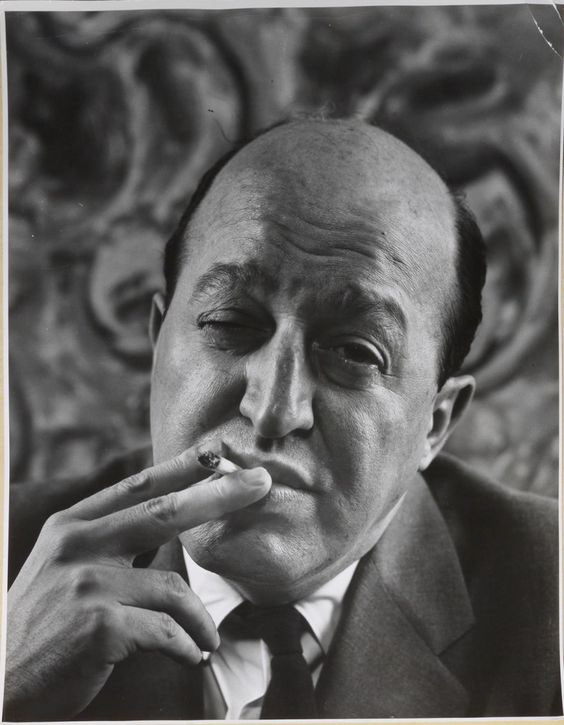

Clement Greenberg

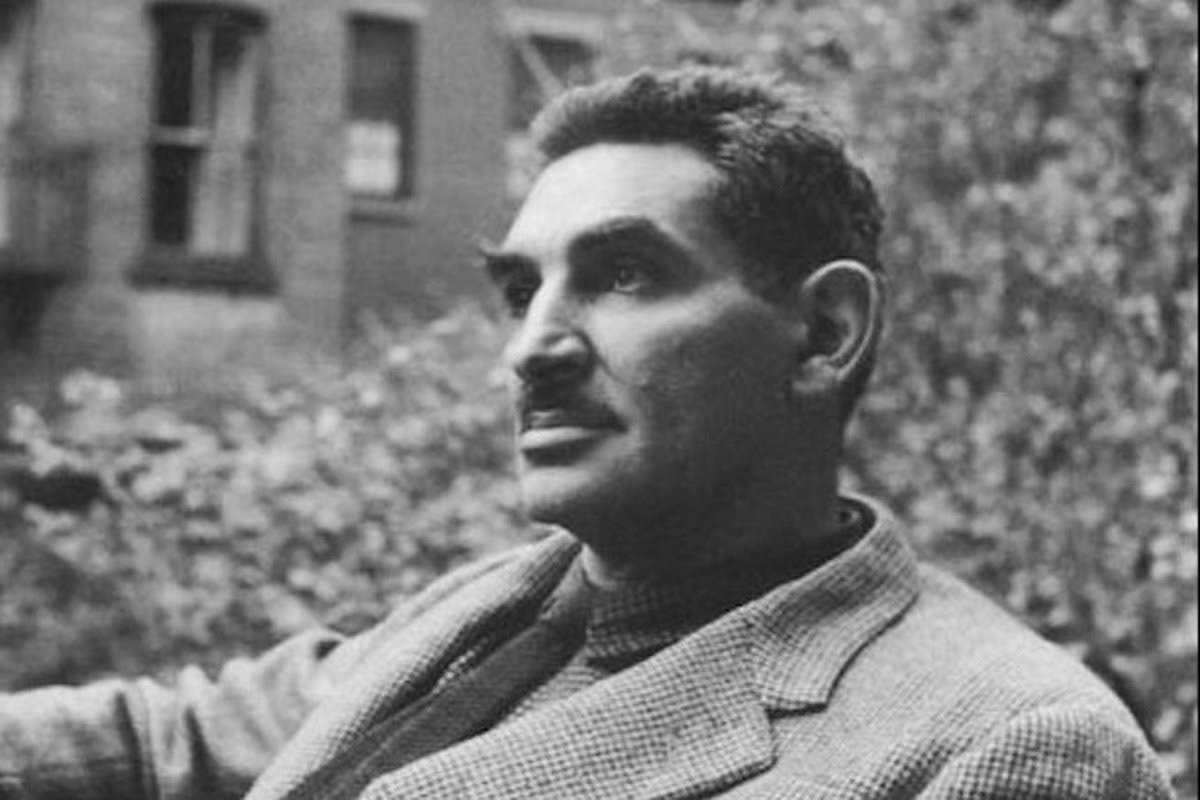

Harold Rosenberg

Thomas Braden

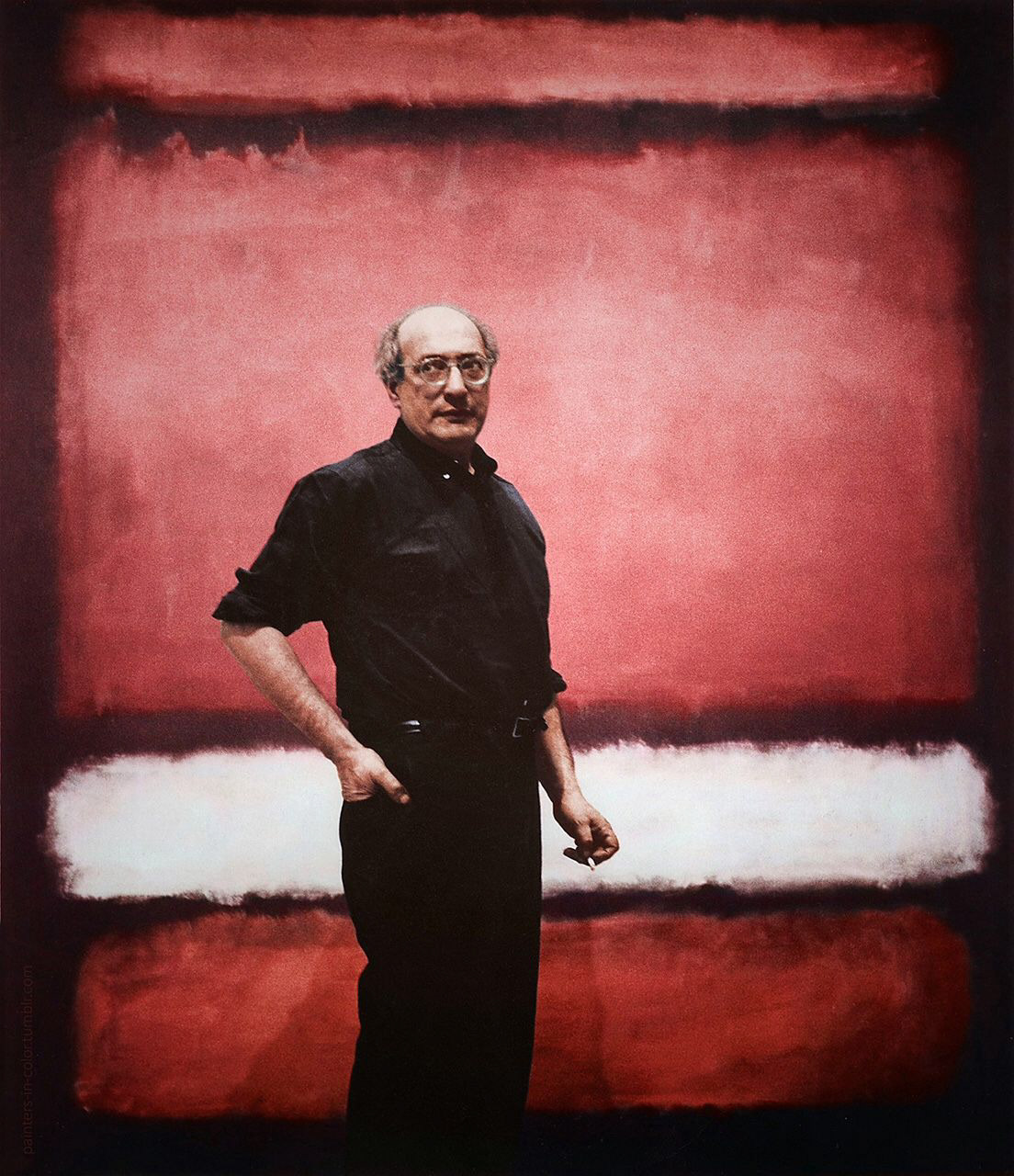

Mark Rothko

Jackson Pollock

Museum of Modern Art

Jackson Pollock, "Convergence," 1952

Socialist Realism: "Roses for Stalin" by Boris Vladimirski, 1949

Socialist Realism: "We Fulfill the Party's Commission!" 1957

Watch the video version of this article